Almost 20 years ago, the UK was at the forefront of digital democracy. The Office of the Deputy Prime Minister (now MGCLG) established a £4m center of excellence on local democracy (called ICELE) and kickstarted a number of cutting edge pilots with local authorities – including some early experiments in online consultation.

Back then the country raised its game but today it feels like much of that head-start has evaporated and many public bodies are peddling backward, re-evaluating the benefits after the drivers and cash dried-up. For example, the Local Democracy Economic Development & Construction Act (2009) was used to formally establish the practice of petitions and online petitioning in local government but few government officers even realise that they have a facility.

The business case has buckled and getting democratic organisations to spend on improving democracy is hard work. Participation is still seen as an add-on to representative democracy, providing additional information for politicians and managers, rather than as an alternative form of democratic deliberation or engagement. The NHS is slashing comms jobs as a priority as it doesn’t recognise their true value.

Moreover, elected members and officers appear to remain committed to the idea that councillors start from the geographic principle: that is, that they are representatives of their wards or divisions. An emphasis and commitment to reinforcing representative democracy means that councils are likely to focus only on those tools and processes that support the electoral process and the subsequent practice of representation, rather than the full range of potential uses.

On the other side of the fence, citizen participation still has a tendency to manifest itself where people are self-interested. Active engagement is stalled Instead of being mobilised through the networks of associations, pressure groups, media and other informal institutions. Just look at what’s happened to the BBC – they once championed citizen engagement through their ‘Action Network’ online platform and the BBC Trust.

It’s not all doom and gloom. Some organisations have taken the opportunity to radically change the way democracy works by shifting the balance of power. For example, we see many more instances of participatory budgeting and citizen assemblies in government but the private sector has been slow to convert and generally still thinks the only time it is necessary to consult is on redundancies.

Consequently we think that local authorities need to be reminded that democracy, and democratic renewal more generally, is worthy of resources.

Principles of success

So what are the ingredients for success? Here is what we’d put in our soup:-

1.Commitment

Leadership and strong commitment to information, consultation and active participation is needed at all levels, from politicians, senior managers and public officials.

- Raise awareness among politicians of their role in promoting open, transparent and accountable policy-making.

- Provide opportunities for information exchange among senior managers

- Provide targeted support to public officials through training, codes of conduct, standards and general awareness raising

2. Rights

Citizens’ rights to access information, provide feedback, be consulted and actively participate in policy-making must be firmly grounded in law or policy. Government obligations to respond to citizens when exercising their rights also must be clearly stated. Independent authorities for oversight, or their equivalent, are essential to enforcing these rights.

- Ensure that public officials know and apply the law:

- Strengthen independent institutions for oversight

- Raise public awareness

3.Clarity

Objectives for, and limits to, information, consultation and active participation during policy-making should be well defined from the outset. The respective roles and responsibilities of citizens (in providing input) and government (in making decisions for which they are accountable) must be clear.

- Avoid creating false expectations: Define, communicate your objectives, and specify commitments and the relative weight to be given to public input.

- Provide full information on where to find relevant background materials, on how to submit comments and on what the process is, as well as on the next steps for decision-making.

4. Opportunity

Public consultation and active participation should be undertaken as early in the policy process as possible to allow for a greater range of policy solutions to emerge and raise the chances of successful implementation.

- Start early in assessing information needs

- Be realistic in building enough time for public information and consultation into decision-making timetables.

- Ensure that the timing of consultation is closely linked to the reality of government decision-making calendars.

5. Objectivity

Information provided by the government during policy-making should be objective, complete and accessible. All citizens should have equal treatment when exercising their rights of access to information and participation.

- Set standards for public information services and products (for instance drafting guidelines).

- Enforce standards through internal peer review and monitoring.

- Ensure access by using multiple channels for information and consultation. Adapt consultation and participation

- procedures to citizens’ needs.

- Establish and uphold rights of appeal by introducing and publicising options for citizens to enforce their rights of access to information, consultation and participation.

6. Resources

- Adequate financial, human and technical resources are needed if democracy initiatives are to be effective.

- Set priorities and allocate sufficient resources to design and conduct the activities, including human, financial and technical resources.

- Build skills through dedicated training programmes, practical handbooks and information-exchange events.

- Promote values of government-citizen relations throughout administration by publicising them and leading by example.

7. Co-ordination

- Initiatives to inform citizens, requesting feedback and consulting them should be coordinated across government. This enhances knowledge management, ensures policy coherence, and avoids duplication. It also reduces the risk of “consultation fatigue”.

- Strengthen co-ordination capacities

- Build networks of public officials responsible for information, consultation and participation activities within the administration.

- Encourage innovation: Identify and disseminate examples of good practice and reward innovative practices.

8. Accountability

Democracy is much about governments’ obligation to account for the use they make of citizens’ inputs received. To increase this accountability, governments need to ensure an open and transparent policy-making process amenable to external scrutiny and review.

- Give clear indications on the timetable for decision-making and how citizens can provide their comments and suggestions and how their input has been assessed and incorporated in the decisions reached.

- Clarify responsibilities and assign specific tasks to individual units or public officials. Ensure that these responsibilities are publicly known.

9. Evaluation

Evaluation is essential in order to adapt to new requirements and changing conditions for policy-making.

- Collect data on key aspects of the information, consultation and participation initiatives.

- Develop appropriate tools for evaluation.

- Engage citizens in evaluating specific events as well as overall government efforts for strengthening government-citizen relations.

10. Active citizenship

To achieve the ultimate goal of democracy, governments can take concrete actions to facilitate citizens’ access to information and participation, raise awareness, and strengthen civic education and skills. They can support capacity building among civil society organisations.

- Invest in civic education for adults and youth.

- Support initiatives undertaken by others with the same goal.

- Foster civil society by developing a supportive legal framework, offering assistance, developing partnerships and providing regular opportunities for dialogue.

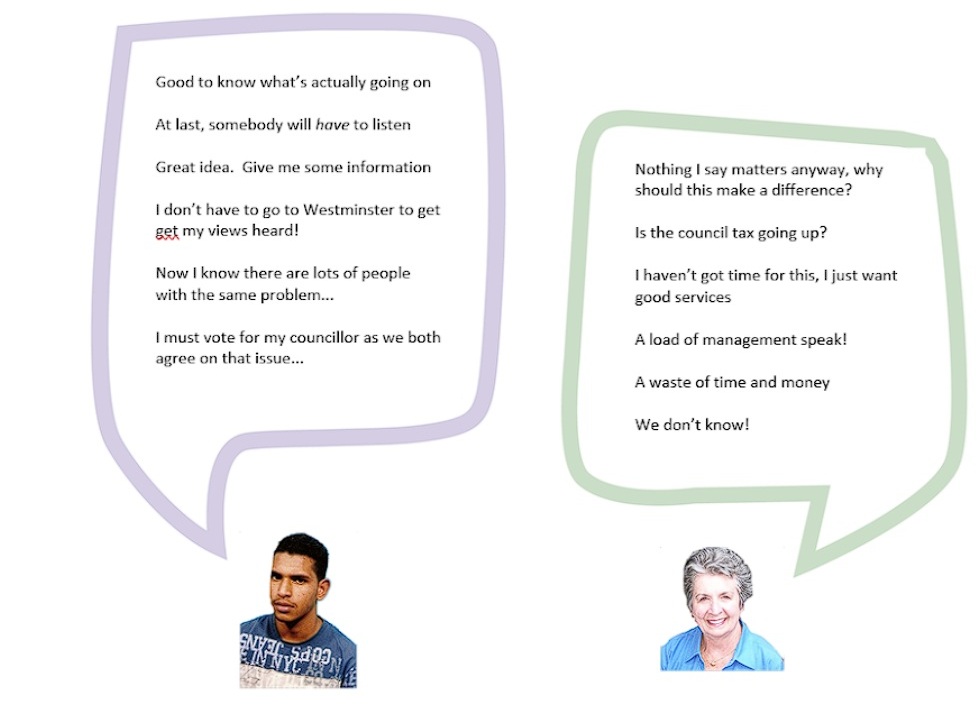

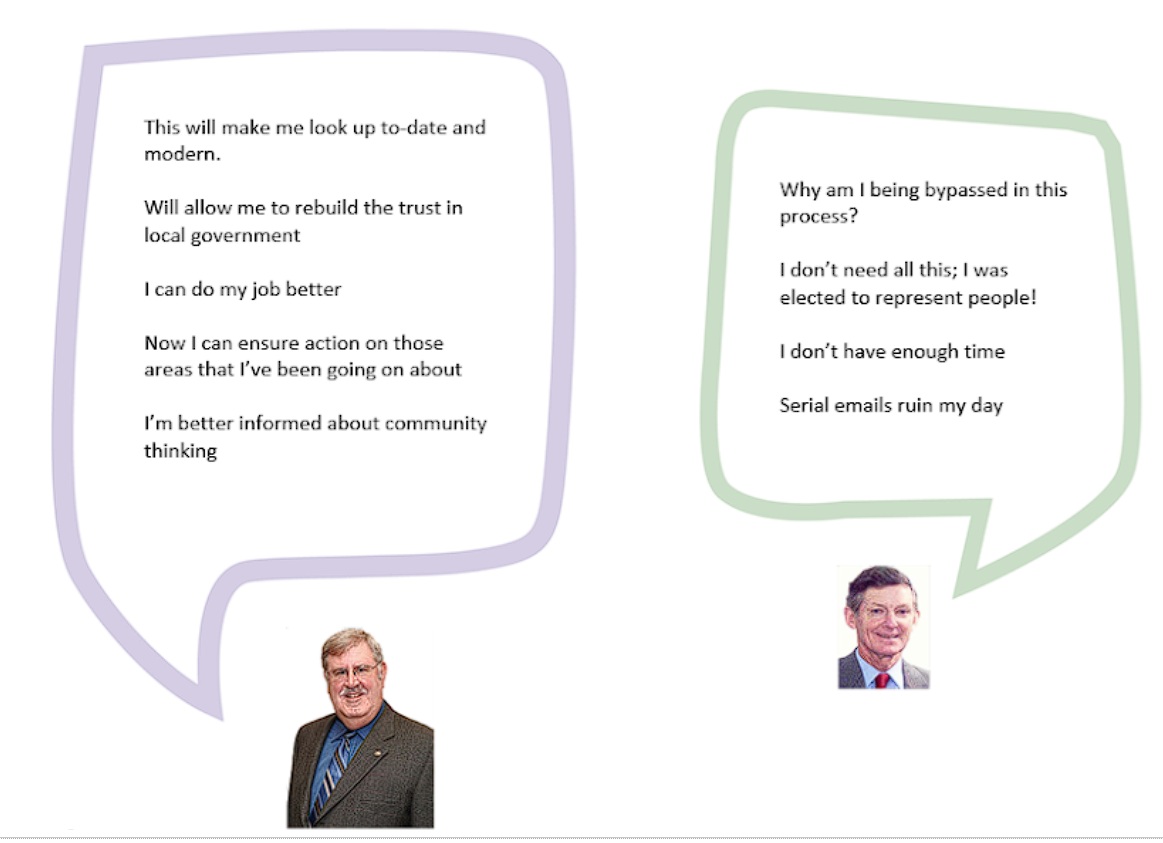

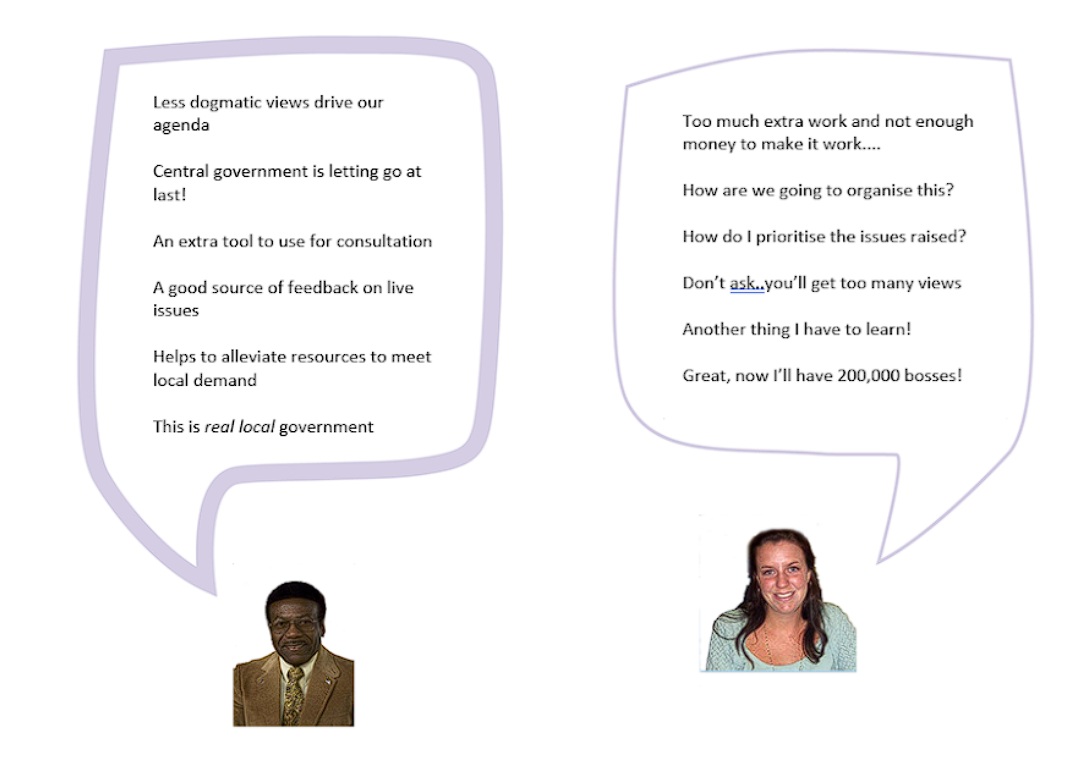

Neatly, one of the government publications 20 years’ ago produced some nice illustrations to depict the conflicted views from the various actors . We’ve recycled them here for your viewing pleasure:-

The divided elected member

The divided council officer

The divided citizen